The Greek translation of the Old Testament made it accessible in the Hellenistic period (c. 300 bce–c. 300 ce) and provided a language for the New Testament and for the Christian liturgy and theology of the first three centuries. The Bible in Latin shaped the thought and life of Western people for a thousand years. People had no bible in their own vernacular.

Throughout history vocally people recounted the Hebrew myths of creation which have superseded the racial mythologies of Latin, Germanic, Slavonic, and all other Western peoples.

Here and there scribes wrote notes in their own language or provided a word for word translation between the lines of the Latin text.

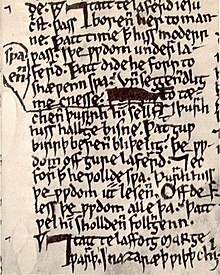

Liber Generationis, the opening page of the Gospel of St. Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels, (Photo credit: British Library)

Already in the 10th century an Old English translation of the Gospels was made in the Lindisfarne Gospels, a manuscript illuminated in the late 7th or 8th century in the Hiberno-Saxon style with a word-for-word gloss inserted between the lines of the Latin text by the scrybe Aldred, Provost of Chester-le-Street. The book was probably made for Eadfrith, the bishop of Lindisfarne from 698 to 721. Attributed to the Northumbrian school, the Lindisfarne Gospels show the fusion of Irish, classical, and Byzantine elements of manuscript illumination and may be considered to be the oldest extant translation of the Gospels into the English language.

The Tower of Babel, from an illustrated manuscript (11th century) containing some Latin excerpts from the Hexateuch. Ælfric was responsible for the preface to Genesis as well as some of its translations. Another copy of the text, without lavish illustrations but including a translation of the Book of Judges, is found in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Laud Misc. 509.

Produced in approximately 990 the Wessex Gospels (also known as the West-Saxon Gospels) are a full translation of the four gospels into a West Saxon dialect of Old English. In 1842 still copies were printed by Richard & John Taylor as the Da Halgan Godspel on Englisc – the Anglo Saxon Version of the Holy gospels. The Cambridge University press brought a version with the Latin text and Lindisfarne Gospels included in 1871-1879.

The Anglo-Saxon prose writer, considered the greatest of his time, Benedictine Abbot Ælfric translated much of the Old Testament into Old English. He was the author of a Latin grammar, hence his nickname Grammaticus, he also wrote Lives of the Saints, Heptateuch (a vernacular language version of the first seven books of the Bible), as well as letters and various treatises.

The book of Genesis up to the story of Abraham and Isaac, along with selections from other books of the first six books of the Hebrew Bible, the Hexateuch, under the directon of Æthelweard were translated in the 11th century, by Ælfric into the vernacular, that is, into Old English.

A page from the Ormulum demonstrating the editing performed over time by Orm (Parkes 1983, pp. 115–16), as well as the insertions of new readings by “Hand B”.

Like its Old English precursor from Ælfric, and Abbot of Eynsham a version in Middle English was reproduced in the 12th century by an Augustinian monk named Orm (or Ormin) at the behest of his brother Brother Walter. It consisted of just under 19,000 lines of early Middle English verse. ‘The Ormulum or Orrmulum)

The motivation was to provide an accessible English text for the benefit of the less educated, which might include some clergy who found it difficult to understand the Latin of the Vulgate, and the parishioners who in most cases would not understand spoken Latin at all (Treharne 2000, p. 273).

We do know that mostly the pastors also gave themselves a paraphrased Gospel reading before going over to their exhortation, because the laity did not understand Latin and there had to be some relation of the sermon to the ‘bible reading’.

At the end of the 13th century a Psalter saw the light in English, which would be a base for Wycliffe version of the English Bible. The theological scholar and advocate of the English reform movement within the Roman Church, Nicholas Of Hereford, who later recanted his unorthodox views and participated in the repression of other reformers, became influenced by Wycliffe, founder of an evangelical Christian group called Lollards. He was entrusted to make a translation of the Old Testament, of which the the major part was completed before a synod in London and his subsequent departure for Rome in 1382.

Long thought to be the work of Wycliffe himself, the Wycliffite translations are now generally believed to be the work of several hands. Nicholas of Hereford is known to have translated a part of the text; John Purvey and perhaps John Trevisa are names that have been mentioned as possible authors.

When the first complete translation of the Bible into English emerged, it became the object of violent controversy because it was inspired by the heretical teachings of John Wycliffe. Intended for the common man, it became the instrument of opposition to ecclesiastical authority.

Archbishop Arundel (1353–1414) initiated against the Lollards (followers of John Wycliffe) a campaign that resulted in the burning of several of them. He summoned a synod of clergy to Oxford in 1408 a synod of clergy summoned to Oxford for discussion of the forbidding of the translation and use of Scripture in the vernacular. The proscription was rigorously enforced, but remained ineffectual.

John Oldcastle being burnt for insurrection and Lollard heresy.

The distinguished soldier and martyred leader of the Lollards, John Oldcastle who gained the friendship of King Henry IV’s son Henry, prince of Wales, was in 1413 indicted by a convocation, presided over by Archbishop Thomas Arundel of Canterbury, for maintaining both Lollard preachers and their opinions. Though he had served as a justice of the peace, and was High Sheriff of Herefordshire in 1406–07 and even had an amicable relationship with the prince of Wales, now Henry V, who regarded Sir John as “one of his most trustworthy soldiers”, which earned him special consideration, he failed to honour the king’s appeals to submit and was brought to trial the same year. Oldcastle declared his readiness to submit to the king “all his fortune in this world” but was firm in his religious beliefs and was hanged over a fire that consumed the gallows, on December 14.

In the course of the 15th century the Wycliffite Bible or Wycliffe’s Bible, which had appeared over a period from approximately 1382 to 1395, achieved wide popularity as is evidenced by the nearly 200 manuscripts extant, most of them copied between 1420 and 1450. The first versions where still following the word order in the Latin text which made them difficult to read. Later versions made more concessions to the native grammar of English so that it was easier for laypersons to comprehend.

In 1526 Peter Schoeffer, who had entered the printing business as the partner of Gutenberg’s creditor, Johann Fust, whose daughter he later married, in the German city of Worms came to print the work of an educated english man from Oxford and Cambridge, who was an impressive scholar, fluent in eight languages, and was ordained as a Christian priest in around 1521. That English scholar, William Tyndale, had previously translated a tract by the humanist who was the greatest scholar of the northern Renaissance Desiderius Erasmus, from Rotterdam, whose writings argued for personal faith: a direct relationship between the individual and God, not one mediated and controlled by the Church hierarchy. Erasmus helped lay the groundwork for the historical-critical study of the past, especially in his studies of the Greek New Testament and the Church Fathers. He was the the first editor of the New Testament, and also an important figure in patristics and classical literature.

For William Tyndale it had become clear that people had more to listen to God His Word than to the words of a church-organisation which was telling people things which were not according to the Words of God. Naturally it was very easy for a church to tell people anything that supposedly would be written in the bible, though they knew it was no Biblical teaching, but by presenting it as such, they could keep the people in control and in their hand.

Four centuries later still many preachers just take verses out of contexts and keep repeating them at the service without ever reading the whole chapter or at least the paragraph, where more clarity could be found. In this way still many churches proclaim un-biblical teachings though people are often not aware of it and continue to stay in that denomination often giving it enough money, being asked to do so by their pastors, not to come into hell (for them a place for eternal torture) .

At the time of Tyndale Christians continued to be governed from Rome by the Pope offering church services in Latin throughout the Christian world, and translation of the Latin Bible into the vernacular, in other words the local language anyone could understand, was actively discouraged and even worse in many countries forbidden.

In England under the 1408 Constitutions of Oxford, it was strictly forbidden to translate the Bible into the native tongue, so that those governing could be sure no uneducated people could come to see what was really written in the bible.

Cardinal Wolsey, Lord Chancellor and Sir Thomas More vigorously enforced this ban in an attempt to prevent the rise of English ‘Lutheranism’.

The only authorised version of the Bible was St Jerome’s Latin translation, known as the ‘Vulgate’, made in the fourth century and understood only by highly-educated people.

Aided by money from Sir Humphrey and others, Tyndale in May 1524, set sail for Germany where he hoped his secret work could be continued in greater safety. There he could work without fear basing his translation on a New Testament in Greek that had recently been complied by Erasmus from several manuscripts older and more authoritative than the Latin Vulgate. By re-translating into English a closer version to the original texts could be created for the English speaking community.

Printing began in Cologne in the summer of 1525, but word of the project soon reached the Dean of Frankfurt. He not only arranged a ban on printing in Cologne but also alerted Cardinal Wolsey to Tyndale’s activities. Tyndale fled with his assistant, William Roy, to Worms, where a pocket-sized edition was the first of two to be completed. By April 1526, Tyndale’s New Testament, pronounced heretical in England, so his Bibles were smuggled into the country in bales of cloth, to being read behind closed doors in England.

Though it did not include all of the books we enjoy today his version was used later on as a base for the versions the Church of England used.

The Bible, translated by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale, 1535 edition.

In 1529 the Yorkshireman and Augustinian friar who was ordained a priest (1514) at Norwich and later became bishop of Exeter, Myles Coverdale, helped William Tyndale translate the Pentateuch in Hamburg and then apparently settled in Antwerp, where he translated the Bible. It was there that he in 1535 compiled and published the first complete (Old Testament and New Testament) Modern English translation of the Bible (cf. Wycliffe’s Bible in manuscript) printed by Merten de Keyser (Martin Lempereur) who also had printed the first complete French Bible translation, in Antwerp. This Coverdale Bible, although allowed to circulate in England, lacked official approval because of its so called heretical tendentiousness and its inadequacy as a translation. A new edition, “overseen and corrected,” was published in England by James Nycholson in Southwark in 1537. Another edition of the same year bore the announcement, “set forth with the king’s most gracious license.” In 1538 a revised edition of Coverdale’s New Testament printed with the Latin Vulgate in parallel columns issued in England was so full of errors that Coverdale promptly arranged for a rival corrected version to appear in Paris. Accordingly, Thomas Cromwell the King’s vice-gerent, or deputy, in spiritual affairs, engaged Coverdale to work in England on a new version, using a revised edition of Tyndale’s work known as Matthew’s Bible. Coverdale’s renewed efforts resulted in the publication in 1539 of the widely accepted Great Bible. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal licence and was therefore the first officially approved Bible translation in English. In edited 1540 Coverdale also edited Cranmer’s Bible.

72 years later an other Royal licensed bible would deliver such an important Bible translation it would become reprinted for centuries, becoming a still preferred version by many.

+

Preceding in Dutch: Broeders en Zusters in Christus door de eeuwen heen #11 Vredelievende waarheidzoekers

Next: Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #2 the King James Bible versions

++

Additional reading

- Biblical literature

- The Anglo-Saxon Version of the Holy Gospels at archive.org

- The Holy Gospels in Anglo-Saxon, Northumbrian, and Old Mercian Versions at archive.org

- Celebrating the Bible in English

- The Bible4Life - a Multimedia Presentation

- Wycliffe Associates supporting underground Bible translators

- Seminar on Bible Translation in Prague

- HalleluYah Scriptures

- Americans really thinking the Messiah Christ had an English name

- Christian clergyman defiling book which did not belong to him

- Codex Sinaiticus

- Codex Sinaiticus available for perusal on the Web

- The Anjou Bible Project

- The NIV and the Name of God

- Why believing the Bible

- Human & Biblical teachings

- Bible & us

+++

Further reading

- Where Words Come From

- Saint Jerome

- Jerome and the Vulgate

- Could Bezae be a response to the Vulgate?

- God’s Word- The Vulgate?

- S. Hieronymus

- #WhyBible

- Many endured Hell to bring us the Bible in English….

- The Middle Ages part 2

- Medieval bling

- The Protestant Deformation

- Rumblings of Reformation: John Wycliffe and the Supremecy of the Word of God

- 1385 Wycliffe: Gen. Cap 1:1-2

- 1385 Wycliffe: Gen. Cap 1:28-30

- 1385 Wycliffe: Gen. Cap 2:6-15

- William Tyndale – 6 October 2015

- William Tyndale: Rebel of the Vernacular Scriptures

- William Tyndale 1

- William Tyndale 2

- Online gallery Sacred texts Tyndale New Testament

- Tindall alias Hitchins Family of North Nibley

- Williams Tyndale: The Experiential Outworking of Sola Scriptura

- William Tyndale On the Law

- Or a Cab Driver

- Translating Tyndale’s Dedication

- William Tyndale & Charles Spurgeon On Sacred Words And Deeds

- Sermon: A Man Who Gave His Life that You Might Have an English Bible

- Desiderius Erasmus

- The Remarkable Erasmus

- Thoughts on Anglicanism

- The Reformation

- A little tale of mediaeval sleeping….

- Skimming, Scanning, and Illiteracy

- helpmate

- Puritan History

- When It Was Unthinkable that the State Would Affirm God

- R.C. Sproul on Understanding Bible Translations

- How to Deepen the Spiritual Life of A Congregation

- Thinking time

- English Historical Fiction Authors: The Christians Are Coming! (The islands of Iona and Lindisfarne)

- Archaeologists Locate Lindisfarne monastery

- A Monk’s Chronicle: 22 August 2016 — A Bridge to Somewhere

- #WordlessWednesday #Lindisfarne Priory & Castle #Photography

- Reign of Terror

- Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne – A Vision For Today

- Lindisfarne – A Holy Island

- Northumberland Coastal Way

- Lindisfarne Island

- Why I Love Lindisfarne, and Why You Should Go Right Now

- Lindisfarne and Leeds

- That’s Not Old English! (how to act like a total tool…and enjoy doing it!)

- Converging Worlds: Cultural Exchanges in Literature and the Written Word (Conference, 20th June)

- English: The Living Language

- A Brief History of the English Language, pt. 12

- The Finale – A Brief History of the English Language

- On the Origins of the word ‘Read’

- dwindle

- wel-þungen

- hālig-mōnaþ

- hærfest-mōnaþ

- Va-etchanan 5776

- Stomp the Yard

- Scripture Celebration

- Languages and Translation

- Meaning of TH House Names

- Incredible! 182 Years Later, SE Asian Group Receives the Gospel in their Language from Wycliffe

- Bible Translation in the Jungle

- Hack On IT

- May 21st

- Double Edged Sword

- What price a Bible?

- How Much Does A Bible Really Cost?

- Handing knowledge down the years

- Today in Christian History: June 10

- 139 You who believe in the Name of the Son of God. 1 John 5:13

- The Conflict Over Different Bible Versions/Part 1

- The Conflict Over Different Bible Versions/Part 6

- Is the King James Version of the Bible the Only Bible Christians Should Trust and Read/Part 2

+++

Bijbelvorsers Webs

Bijbelvorsers Webs Belgische Vrije Christadelphians / Belgian Free Christadelphians – Old Google Main Website

Belgische Vrije Christadelphians / Belgian Free Christadelphians – Old Google Main Website Christadelphian Ecclesia

Christadelphian Ecclesia Hoop tot Leven – Redding in Christus

Hoop tot Leven – Redding in Christus

Comments on: "Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible" (20)

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] evidence in their multipart series of blog posts entitled, Old and newer King James Versions and other translations. They say the King James is wrong, but they never address the question, “What is […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible: looking at the Old English translations of the Gospels (West-Saxon Gospels, Lindisfarne Gospels), the 11th century Hexateuch translation, and other predecessors which were also used as a base for the Authorised King James Bible of 1611, like the 15th century Wycliffite Bible, 16th century Tyndale’s New Testament and Myles Coverdale Bible. […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike

[…] Old and newer King James Versions and other translations #1 Pre King James Bible […]

LikeLike